ECE 5745 Tutorial 5: Synopsys/Cadence ASIC Tools

- Author: Christopher Batten, (Updated by Jack Brzozowski)

- Date: March 2, 2021 (January 8, 2022)

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Nangate 45nm Standard-Cell Library

- PyMTL3-Based Testing, Simulation, Translation

- Using Synopsys VCS for 4-State RTL Simulation

- Using Synopsys Design Compiler for Synthesis

- Using Synopsys VCS for Fast Functional Gate-Level Simulation

- Using Cadence Innovus for Place-and-Route

- Using Synopsys VCS for Back-Annotated Gate-Level Simulation

- Using Synopsys PrimeTime for Power Analysis

- Using Verilog RTL Models

- To Do On Your Own

Introduction

This tutorial will discuss the various views that make-up a standard-cell library and then illustrate how to use a set of Synopsys and Cadence ASIC tools to map an RTL design down to these standard cells and ultimately silicon. The tutorial will discuss the key tools used for synthesis, place-and-route, simulation, and power analysis. This tutorial requires entering commands manually for each of the tools to enable students to gain a better understanding of the detailed steps involved in this process. The next tutorial will illustrate how this process can be automated to facilitate rapid design-space exploration. This tutorial assumes you have already completed the tutorials on Linux, Git, PyMTL3, and Verilog.

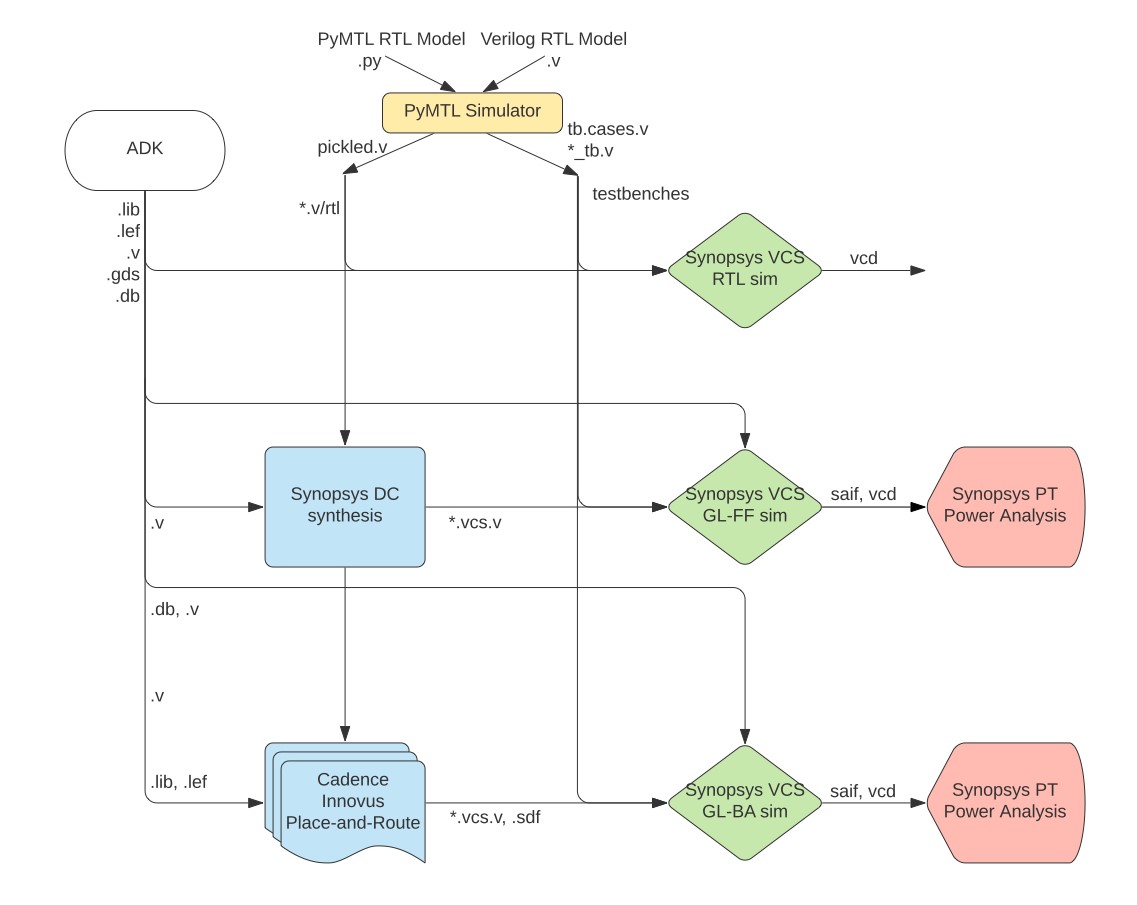

The following diagram illustrates the five primary tools we will be using in ECE 5745 along with a few smaller secondary tools. Notice that the ASIC tools all require various views from the standard-cell library.

-

We use the PyMTL3 framework to test, verify, and evaluate the execution time (in cycles) of our design. This part of the flow is very similar to the flow used in ECE 4750. Note that we can write our RTL models in either PyMTL3 or Verilog, but we will always use PyMTL3 for the test harnesses, simulation drivers, and high-level modeling. Once we are sure our design is working correctly, we can then start to push the design through the flow. The ASIC flow requires Verilog RTL as an input, so we can use PyMTL3’s automatic translation tool to translate PyMTL3 RTL models into Verilog RTL.

-

We use Synopsys VCS to compile and run both 4-state RTL and gate-level simulations. These simulations help us to build confidence in our design as we push our designs through different stages of the flow. From these simulations, we also generate waveforms in

.vcd(Verilog Change Dump) format, and we usevcd2saifto convert these waveforms into per-net average activity factors stored in.saifformat. These activity factors will be used for power analysis. Gate-level simulation is an extremely valuable tool for ensuring the tools did not optimize something away which impacts the correctness of the design, and also provides an avenue for obtaining a more accurate power analysis than RTL simulation. Though Static Timing Analysis (STA) is much better because it analyzes all paths, GL simulation also serves as a backup to check for hold and setup time violations (chip designers must be paranoid!) -

We use Synopsys Design Compiler (DC) to synthesize our design, which means to transform the Verilog RTL model into a Verilog gate-level netlist where all of the gates are selected from the standard-cell library. We need to provide Synopsys DC with abstract logical and timing views of the standard-cell library in

.dbformat. In addition to the Verilog gate-level netlist, Synopsys DC can also generate a.ddcfile which contains information about the gate-level netlist and timing, and this.ddcfile can be inspected using Synopsys Design Vision (DV). -

We use Cadence Innovus to place-and-route our design, which means to place all of the gates in the gate-level netlist into rows on the chip and then to generate the metal wires that connect all of the gates together. We need to provide Cadence Innovus with the same abstract logical and timing views used in Synopsys DC, but we also need to provide Cadence Innovus with technology information in

.lef, and.captableformat and abstract physical views of the standard-cell library also in.lefformat. Cadence Innovus will generate an updated Verilog gate-level netlist, a.speffile which contains parasitic resistance/capacitance information about all nets in the design, and a.gdsfile which contains the final layout. The.gdsfile can be inspected using the open-source Klayout GDS viewer. Cadence Innovus also generates reports which can be used to accurately characterize area and timing. -

We use Synopsys PrimeTime (PT) to perform power analysis of our design. We need to provide Synopsys PT with the same abstract logical, timing, and power views used in Synopsys DC and Cadence Innovus, but in addition we need to provide switching activity information for every net in the design (which comes from the

.saiffile), and capacitance information for every net in the design (which comes from the.speffile). Synopsys PT puts the switching activity, capacitance, clock frequency, and voltage together to estimate the power consumption of every net and thus every module in the design, and these estimates are captured in various reports.

Extensive documentation is provided by Synopsys and Cadence for these ASIC tools. We have organized this documentation and made it available to you on the public course webpage. The username/password was distributed during lecture.

The first step is to source the setup script, clone this repository from GitHub, and define an environment variable to keep track of the top directory for the project.

% source setup-ece5745.sh

% mkdir -p $HOME/ece5745

% cd $HOME/ece5745

% git clone git@github.com:cornell-ece5745/ece5745-tut5-asic-tools

% cd ece5745-tut5-asic-tools

% TOPDIR=$PWD

Nangate 45nm Standard-Cell Library

Before you can gain access to a standard-cell library, you need to gain access to a “physical design kit” (PDK). A PDK includes all of the design files required for full-custom circuit design for a specific technology. So this will include a design-rule manual as well as SPICE circuit models for transistors and other devices. Gaining access to a real PDK is difficult. It requires negotiating with the foundry and signing multiple non-disclosure agreements. So in this course we will be using the FreePDK45 PDK:

- https://www.eda.ncsu.edu/wiki/FreePDK45

This is an open PDK for a “fake” technology. It was created by universities using publically available data on several different commercial 45nm processes. This means you cannot actually tapeout a chip using this PDK, but the technology is representative enough to provide reasonable area, energy, and timing estimates for research and teaching purposes. You can find the FreePDK45 PDK installed here:

% cd $ADK_PKGS/freepdk-45nm/pkgs/FreePDK45-1.4

A standard-cell designer will use the PDK to implement the standard-cell

library. A standard-cell library is a collection of combinational and

sequential logic gates that adhere to a standardized set of logical,

electrical, and physical policies. For example, all standard cells are

usually the same height, include pins that align to a predetermined

vertical and horizontal grid, include power/ground rails and nwells in

predetermined locations, and support a predetermined number of drive

strengths. A standard-cell designer will usually create a high-level

behavioral specification (in Verilog), circuit schematics (in SPICE), and

the actual layout (in .gds format) for each logic gate. The Synopsys

and Cadence tools do not actually use these low-level implementations,

since they are actually too detailed. Instead these tools use abstract

views of the standard cells, which capture logical functionality,

timing, geometry, and power usage at a much higher level.

Just like with a PDK, gaining access to a real standard-cell library is difficult. It requires gaining access to the PDK first, negotiating with a company which makes standard cells, and usually signing more non-disclosure agreements. In this course, we will be using the Nangate 45nm standard-cell library which is based on the open FreePDK45 PDK.

Nangate is a company which makes a tool to automatically generate standard-cell libraries, so they have made this library publically available a way to demonstrate their tool. Since it is an open library it is a great resource for research and teaching. Even though the standard-cell library is based on a “fake” 45nm PDK, the library provides a very reasonable estimate of a real commercial standard library in a real 45nm technology. In this section, we will take a look at both the low-level implementations and high-level views of the Nangate standard-cell library.

A standard-cell library distribution can contain gigabytes of data in thousands of files. For example, here is the distribution for the Nangate standard-cell library.

% cd $ADK_PKGS/freepdk-45nm/pkgs/NangateOpenCellLibrary_PDKv1_3_v2010_12

To simplify using the Nangate standard-cell library in this course, we have created a much smaller set of well-defined symlinks which point to just the key files we want to use in this course. We call this collection of symlinks an “ASIC design kit” (ADK). Here is the directory which contains these symlinks.

% cd $ECE5745_STDCELLS

% ls

pdk-models.sp # spice models for transistors

rtk-stream-out.map # gds layer map

rtk-tech.lef # interconnect technology information

rtk-tech.tf # interconnect technology information

rtk-typical.captable # interconnect technology information

stdcells.spi # circuit schematics for each cell

stdcells.gds # layout for each cell

stdcells.v # behavioral specification for each cell

stdcells-lpe.spi # circuit schematics with parasitics for each cell

stdcells.lib # abstract logical, timing, power view for each cell (typical)

stdcells-bc.lib # best case .lib

stdcells-wc.lib # worst case .lib

stdcells.lef # abstract physical view for each cell

stdcells.db # binary compiled version of .lib file

stdcells.mwlib # Milkyway database built from .lef file

stdcells-databook.pdf # standard-cell library databook

klayout.lyp # layer settings for Klayout

Let’s begin by looking at the schematic for a 3-input NAND cell (NAND3_X1).

% less -p NAND3_X1 $ECE5745_STDCELLS/stdcells.spi

.SUBCKT NAND3_X1 A1 A2 A3 ZN VDD VSS

*.PININFO A1:I A2:I A3:I ZN:O VDD:P VSS:G

*.EQN ZN=!((A1 * A2) * A3)

M_i_2 net_1 A3 VSS VSS NMOS_VTL W=0.415000U L=0.050000U

M_i_1 net_0 A2 net_1 VSS NMOS_VTL W=0.415000U L=0.050000U

M_i_0 ZN A1 net_0 VSS NMOS_VTL W=0.415000U L=0.050000U

M_i_5 ZN A3 VDD VDD PMOS_VTL W=0.630000U L=0.050000U

M_i_4 VDD A2 ZN VDD PMOS_VTL W=0.630000U L=0.050000U

M_i_3 ZN A1 VDD VDD PMOS_VTL W=0.630000U L=0.050000U

.ENDS

For students with a circuits background, there should be no surprises

here, and for those students with less circuits background we will cover

basic static CMOS gate design later in the course. Essentially, this

schematic includes three NMOS transistors arranged in series in the

pull-down network, and three PMOS transistors arranged in parallel in the

pull-up network. The PMOS transistors are larger than the NMOS

transistors (see W= parameter) because the mobility of holes is less

than the mobility of electrons.

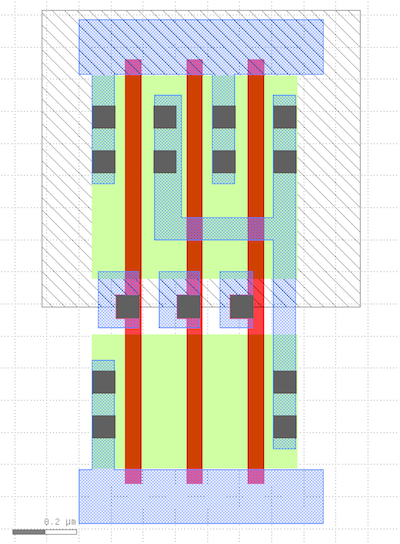

Now let’s look at the layout for the 3-input NAND cell using the open-source Klayout GDS viewer.

% klayout -l $ECE5745_STDCELLS/klayout.lyp $ECE5745_STDCELLS/stdcells.gds

Note that we are using the .lyp file which is a predefined layer color

scheme that makes it easier to view GDS files. To view the 3-input NAND

cell, find the NAND3X1 cell in the left-hand cell list, and then choose

_Display > Show as New Top from the menu. Here is a picture of the

layout for this cell.

Diffusion is green, polysilicon is red, contacts are solid dark blue, metal 1 (M1) is blue, and the nwell is the large gray rectangle over the top half of the cell. All standard cells will be the same height and have the nwell in the same place. Notice the three NMOS transistors arranged in series in the pull-down network, and three PMOS transistors arranged in parallel in the pull-up network. The power rail is the horizontal strip of M1 at the top, and the ground rail is the horizontal strip of M1 at the bottom. All standard cells will have the power and ground rails in the same place so they will connect via abutment if these cells are arranged in a row. Although it is difficult to see, the three input pins and one output pin are labeled squares of M1, and these pins are arranged to be on a predetermined grid.

Now let’s look at the Verilog behavioral specification for the 3-input NAND cell.

% less -p NAND3_X1 $ECE5745_STDCELLS/stdcells.v

module NAND3_X1 (A1, A2, A3, ZN);

input A1;

input A2;

input A3;

output ZN;

not(ZN, i_8);

and(i_8, i_9, A3);

and(i_9, A1, A2);

specify

(A1 => ZN) = (0.1, 0.1);

(A2 => ZN) = (0.1, 0.1);

(A3 => ZN) = (0.1, 0.1);

endspecify

endmodule

Note that the Verilog implementation of the 3-input NAND cell looks

nothing like the Verilog we used in ECE 4750. This cell is implemented

using Verilog primitive gates (e.g., not, and) and it includes a

specify block which is used for advanced gate-level simulation with

back-annotated delays.

We can use sophisticated tools to extract detailed parasitic resistance and capacitance values from the layout, and then we can add these parasitics to the circuit schematic to create a much more accurate model for experimenting with the circuit timing and power. Let’s look at a snippet of the extracted circuit for the 3-input NAND cell:

% less -p NAND3_X1 $ECE5745_STDCELLS/stdcells-lpe.spi

.SUBCKT NAND3_X1 VDD VSS A3 ZN A2 A1

*.PININFO VDD:P VSS:G A3:I ZN:O A2:I A1:I

*.EQN ZN=!((A1 * A2) * A3)

M_M3 N_ZN_M0_d N_A3_M0_g N_VDD_M0_s VDD PMOS_VTL W=0.630000U L=0.050000U

M_M4 N_VDD_M1_d N_A2_M1_g N_ZN_M0_d VDD PMOS_VTL W=0.630000U L=0.050000U

M_M5 N_ZN_M2_d N_A1_M2_g N_VDD_M1_d VDD PMOS_VTL W=0.630000U L=0.050000U

M_M0 net_1 N_A3_M3_g N_VSS_M3_s VSS NMOS_VTL W=0.415000U L=0.050000U

M_M1 net_0 N_A2_M4_g net_1 VSS NMOS_VTL W=0.415000U L=0.050000U

M_M2 N_ZN_M5_d N_A1_M5_g net_0 VSS NMOS_VTL W=0.415000U L=0.050000U

C_x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_c0 x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_39 VSS 3.704e-17

C_x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_c1 x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_36 VSS 2.74884e-18

C_x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_c2 x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_26 VSS 2.61603e-16

C_x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_c3 N_VDD_M1_d VSS 6.57971e-17

C_x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_c4 x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_19 VSS 1.89932e-17

C_x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_c5 x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_18 VSS 3.74888e-17

C_x_PM_NAND3_X1%VDD_c6 N_VDD_M0_s VSS 3.64134e-17

...

.ENDS

The full model is a couple of hundred lines long, so you can see how

detailed this model is! The ASIC tools do not really need this much

detail. We can use a special set of tools to create a much higher level

abstract view of the timing and power of this circuit suitable for use by

the ASIC tools. Essentially, these tools run many, many circuit-level

simulations to create characterization data stored in a .lib (Liberty)

file. Let’s look at snippet of the .lib file for the 3-input NAND cell.

% less -p NAND3_X1 $ECE5745_STDCELLS/stdcells.lib

cell (NAND3_X1) {

drive_strength : 1;

area : 1.064000;

cell_leakage_power : 18.104768;

leakage_power () {

when : "!A1 & !A2 & !A3";

value : 3.318854;

}

...

pin (A1) {

direction : input;

related_power_pin : "VDD";

related_ground_pin : "VSS";

capacitance : 1.590286;

fall_capacitance : 1.562033;

rise_capacitance : 1.590286;

}

...

pin (ZN) {

direction : output;

related_power_pin : "VDD";

related_ground_pin : "VSS";

max_capacitance : 58.364900;

function : "!((A1 & A2) & A3)";

timing () {

related_pin : "A1";

timing_sense : negative_unate;

cell_fall(Timing_7_7) {

index_1 ("0.00117378,0.00472397,0.0171859,0.0409838,0.0780596,0.130081,0.198535");

index_2 ("0.365616,1.823900,3.647810,7.295610,14.591200,29.182500,58.364900");

values ("0.0106270,0.0150189,0.0204521,0.0312612,0.0528211,0.0959019,0.182032", \

"0.0116171,0.0160692,0.0215549,0.0324213,0.0540285,0.0971429,0.183289", \

"0.0157475,0.0207077,0.0261030,0.0369216,0.0585239,0.101654,0.187820", \

"0.0193780,0.0263217,0.0337702,0.0462819,0.0677259,0.110616,0.196655", \

"0.0218025,0.0305247,0.0399593,0.0560603,0.0822203,0.125293,0.210827", \

"0.0229784,0.0334449,0.0447189,0.0640615,0.0959700,0.146382,0.231434", \

"0.0227986,0.0349768,0.0480836,0.0705081,0.107693,0.167283,0.259623");

}

...

internal_power () {

related_pin : "A1";

fall_power(Power_7_7) {

index_1 ("0.00117378,0.00472397,0.0171859,0.0409838,0.0780596,0.130081,0.198535");

index_2 ("0.365616,1.823900,3.647810,7.295610,14.591200,29.182500,58.364900");

values ("0.523620,0.538965,0.551079,0.556548,0.561151,0.564018,0.564418", \

"0.459570,0.484698,0.509668,0.529672,0.543887,0.554682,0.559331", \

"0.434385,0.457202,0.470452,0.498312,0.517651,0.538469,0.550091", \

"0.728991,0.630651,0.581024,0.559124,0.551408,0.553714,0.557387", \

"1.306597,1.153240,1.010684,0.831268,0.727155,0.657699,0.616287", \

"2.170611,1.965158,1.760932,1.459438,1.140559,0.930355,0.781393", \

"3.276307,3.084566,2.831754,2.426623,1.913607,1.439055,1.113950");

}

...

}

...

}

This is just a small subset of the information included in the .lib

file for this cell. We will talk more about the details of such .lib

files later in the course, but you can see that the .lib file contains

information about area, leakage power, capacitance of each input pin,

logical functionality, and timing. Units for all data is provided at the

top of the .lib file. In this snippet you can see that the area of the

cell is 1.064 square micron and the leakage power is 18.1nW. The

capacitance for the input pin A1 is 1.59fF, although there is

additional data that captures how the capacitance changes depending on

whether the input is rising or falling. The output pin ZN implements

the logic equation !((A1 & A2) & A3) (i.e., a three-input NAND gate).

Data within the .lib file is often represented using one- or

two-dimensional lookup tables (i.e., a values table). You can see two

such tables in the above snippet.

Let’s start by focusing on the first table. This table captures the delay

from input pin A1 to output pin ZN as a function of two parameters:

the input transition time (horizontal direction in lookup table) and the

load capacitance (vertical direction in lookup table). Note that this

delay is when ZN is “falling” (i.e., when it is transitioning from high

to low). There is another table for the delay when ZN is rising, and

there are additional tables for every input. Gates are slower when the

inputs take longer to transition and/or when they are driving large

output loads. Each entry in the lookup table reflects characterization of

one or more detailed circuit-level simulations. So in this example the

delay from input pin A1 to output pin ZN is 16ps when the input

transition rate is 4.7ps and the output load is 1.82fF. This level of

detail can enable very accurate static timing analysis of our designs.

Let’s now focus on the second table. This table captures the internal power, which is the power consumed within the gate itself, again as a function of two paramers: the input transition time (horizontal direction in lookup table) and the load capacitance (vertical direction in lookup table). Each entry in the lookup table is calculated by measuring the current drawn from the power supply during a detailed SPICE simulation and subtracting any current used to charge the output load. In other words all of the energy that is not consumed charging up the output load is considered internal energy. Note that sometimes the internal power is negative. This is simply due to how we account for energy. We can either assume all energy is consumed only when the output node is charged and no energy is consumed when the output node is discharged, or we can assume half the energy is consumed when the output is node is charged and half the energy is consumed when the output node is discharged in which case you will sometimes see negative internal power.

Note that some of the ASIC tools actually do not use the .lib file

directly, but instead use a pre-compiled binary version of the .lib

file stored in .db format. The binary .db file is usually much more

compact that the text .lib file. The .lib file captures the abstract

logical, timing, and power aspects of the standard-cell library, but it

does not capture the physical aspects of the standard-cell library. While

the ASIC tools could potentially use the .gds file directly, the ASIC

tools do not really need this much detail. We can use a special set of

tools to create a much higher level abstract view of the physical aspects

of the cell suitable for use by the ASIC tools. These tools create .lef

files. Let’s look at snippet of the the .lef file for the 3-input NAND

cell.

% less -p NAND3_X1 $ECE5745_STDCELLS/stdcells.lef

MACRO NAND3_X1

CLASS core ;

FOREIGN NAND3_X1 0.0 0.0 ;

ORIGIN 0 0 ;

SYMMETRY X Y ;

SITE FreePDK45_38x28_10R_NP_162NW_34O ;

SIZE 0.76 BY 1.4 ;

PIN A1

DIRECTION INPUT ;

ANTENNAPARTIALMETALAREA 0.0175 LAYER metal1 ;

ANTENNAPARTIALMETALSIDEAREA 0.0715 LAYER metal1 ;

ANTENNAGATEAREA 0.05225 ;

PORT

LAYER metal1 ;

POLYGON 0.44 0.525 0.54 0.525 0.54 0.7 0.44 0.7 ;

END

END A1

PIN ZN

DIRECTION OUTPUT ;

ANTENNAPARTIALMETALAREA 0.1352 LAYER metal1 ;

ANTENNAPARTIALMETALSIDEAREA 0.4992 LAYER metal1 ;

ANTENNADIFFAREA 0.197925 ;

PORT

LAYER metal1 ;

POLYGON 0.235 0.8 0.605 0.8 0.605 0.15 0.675 0.15

0.675 1.25 0.605 1.25 0.605 0.87 0.32 0.87 0.32 1.25 0.235 1.25 ;

END

END ZN

PIN VDD

DIRECTION INOUT ;

USE power ;

SHAPE ABUTMENT ;

PORT

LAYER metal1 ;

POLYGON 0 1.315 0.04 1.315 0.04 0.975 0.11 0.975 0.11 1.315

0.415 1.315 0.415 0.975 0.485 0.975 0.485 1.315 0.76 1.315 0.76 1.485 0 1.485 ;

END

END VDD

...

END NAND3_X1

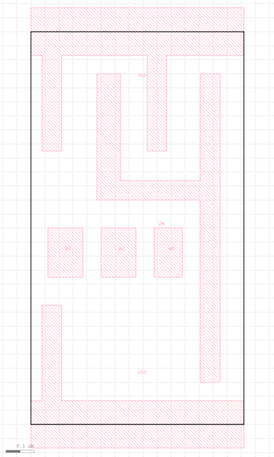

This is just a small subset of the information included in the .lef

file for this cell. You can see the .lef file includes information on

the dimensions of the cell and the location and dimensions of both

power/ground and signal pins. The file also includes information on

“obstructions” (or blockages) indicated with a OBS entry. Take a look

at the NAND4_X4 gate to see an obstruction. These are regions of the cell

which should not be used by the ASIC tools. For example, if a cell needs

to use metal 2 (M2), it would create a blockage on M2 so that the ASIC

tools know not to route any M2 wires in that area. You can use Klayout to

view .lef files as well.

% klayout

Choose File > Import > LEF from the menu. Navigate to the

stdcells.lef file. Here is a picture of the .lef for this cell.

If you compare the .lef to the .gds you can see that the .lef is a

much simpler representation that only captures the boundary, pins, and

obstructions.

The standard-cell library also includes several files (e.g.,

rtk-tech.tf, rtk-tech.lef, rtk-typical.captable) that capture

information about the metal interconnect including the wire width, pitch,

and parasitics. For example, let’s take a look at the .captable file:

% less -p M1 $ECE5745_STDCELLS/rtk-typical.captable

LAYER M1

MinWidth 0.07000

MinSpace 0.06500

# Height 0.37000

Thickness 0.13000

TopWidth 0.07000

BottomWidth 0.07000

WidthDev 0.00000

Resistance 0.38000

END

...

M1

width(um) space(um) Ctot(Ff/um) Cc(Ff/um) Carea(Ff/um) Cfrg(Ff/um)

0.070 0.052 0.1986 0.0723 0.0311 0.0115

0.070 0.065 0.1705 0.0509 0.0311 0.0143

0.070 0.200 0.1179 0.0115 0.0311 0.0319

0.070 0.335 0.1150 0.0030 0.0311 0.0388

0.070 0.470 0.1148 0.0009 0.0311 0.0409

0.070 0.605 0.1147 0.0002 0.0311 0.0416

0.070 0.740 0.1147 0.0001 0.0311 0.0417

This file contains information about the minimum dimenisions of wires on M1 and the resistance of these wires. It also contains a table of wire capacitances with different rows for different wire widths and spacings. The ASIC tools can use this kind of technology information to optimize and analyze the design.

Finally, a standard-cell library will always include a databook, which is a document that describes the details of every cell in the library. Take a few minutes to browse through the Nangate standard-cell library databook located on the class Canvas page here:

- https://canvas.cornell.edu/files/3153288/download

PyMTL3-Based Testing, Simulation, Translation

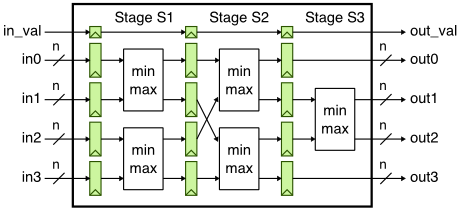

Our goal in this tutorial is to generate layout for the sort unit from the PyMTL3 tutorial using the ASIC tools. As a reminder, the sort unit takes as input four integers and a valid bit and outputs those same four integers in increasing order with the valid bit. The sort unit is implemented using a three-stage pipelined, bitonic sorting network and the datapath is shown below.

Let’s start by running the tests for the sort unit and note that the

tests for the SortUnitStructRTL will fail.

% mkdir -p $TOPDIR/sim/build

% cd $TOPDIR/sim/build

% pytest ../tut3_pymtl/sort

% pytest ../tut3_pymtl/sort --test-verilog --dump-vtb

You can just copy over your implementation of the MinMaxUnit from when

you completed the PyMTL3 tutorial. If you have not completed the PyMTL3

tutorial then you might want to go back and do that now. Basically the

MinMaxUnit should look like this:

from pymtl3 import *

class MinMaxUnit( Component ):

# Constructor

def construct( s, nbits ):

s.in0 = InPort ( nbits )

s.in1 = InPort ( nbits )

s.out_min = OutPort( nbits )

s.out_max = OutPort( nbits )

@update

def block():

if s.in0 >= s.in1:

s.out_max @= s.in0

s.out_min @= s.in1

else:

s.out_max @= s.in1

s.out_min @= s.in0

# Line tracing

def line_trace( s ):

return f"{s.in0}|{s.in1}(){s.out_min}|{s.out_max}"

The --test-verilog command line option tells the PyMTL3 framework to

first translate the sort unit into Verilog, and then import it back

into PyMTL3 to verify that the translated Verilog is itself correct. With

the --test-verilog command line option, PyMTL3 will skip tests that are

not for verifying RTL. The dump_vtb command line option tells PyMTL3 to

dump the Verilog Testbench. While we can do RTL simulation using Python,

we need to translate our testbenches to Verilog so that we can use

Synopsys VCS to do 4-state and gate-level simulation. Let’s look at a

testbench cases file generated from using the --dump-vtb flag.

% cd $TOPDIR/sim/build

% cat SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_test_basic_tb.v.cases

`T('h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0);

`T('h04,'h02,'h03,'h01,'h1,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0);

`T('h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0);

`T('h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0);

`T('h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0,'h01,'h02,'h03,'h04,'h1);

`T('h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0);

`T('h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0);

`T('h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0);

`T('h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h00,'h0);

This file is generated by logging the inputs and outputs of your PyMTL3 RTL simulation each cycle, and it will be passed into a Verilog testbench runner that will use these values to set the inputs each cycle, and to verify the outputs each cycle. So note that when we utilize these testbenches later on, we are running a simulation that is simply confirming that we acheive the same behavior as the RTL simulation we run in PyMTL3, and it is not actually using any assertions you wrote in your Python tests for your design. Therefore, it is important that your RTL simulations pass in PyMTL3 before you move on to other simulations. Also take a look at the testbench itself to get a sense for how it works. It essentially instantiates your top module as ‘DUT’, sets the inputs, and performs a check every cycle on the outputs.

% less SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_test_basic_tb.v

After running the tests we use the sort unit simulator to do the final

translation into Verilog and to dump the vtb file that will allow us

to do 4-state RTL simulation using Synopsys VCS.

% cd $TOPDIR/sim/build

% ../tut3_pymtl/sort/sort-sim --impl rtl-struct --stats --translate --dump-vtb

num_cycles = 106

num_cycles_per_sort = 1.06

Take a moment to open up the translated Verilog which should be in a file

named SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8__pickled.v. Try to see how both the structural

composition and the behavioral modeling translates into Verilog. Here is

an example of the translation for the MinMaxUnit. Notice how PyMTL3 will

output the source Python embedded as a comment in the corresponding

translated Verilog.

% cd $TOPDIR/sim/build

% less SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8__pickled.v

// PyMTL Component MinMaxUnit Definition

// At .../sim/tut3_pymtl/sort/MinMaxUnit.py

module MinMaxUnit__nbits_8

(

input logic [0:0] clk,

input logic [7:0] in0,

input logic [7:0] in1,

output logic [7:0] out_max,

output logic [7:0] out_min,

input logic [0:0] reset

);

// PyMTL Update Block Source

// At /home/sj634/workspace/ece5745-labs/sim/tut3_pymtl/sort/MinMaxUnit.py:26

// @update

// def block():

//

// if s.in0 >= s.in1:

// s.out_max @= s.in0

// s.out_min @= s.in1

// else:

// s.out_max @= s.in1

// s.out_min @= s.in0

always_comb begin : block

if ( in0 >= in1 ) begin

out_max = in0;

out_min = in1;

end

else begin

out_max = in1;

out_min = in0;

end

end

endmodule

The Verilog module name includes a suffix to make it unique for a specific set of parameters. Although we hope students will not need to actually open up this translated Verilog it is occasionally necessary. For example, PyMTL3 is not perfect and can translate incorrectly which might require looking at the Verilog to see where it went wrong. Other steps in the ASIC flow might refer to an error in the translated Verilog which will also require looking at the Verilog to figure out why the other steps are going wrong. While we try and make things as automated as possible, students will eventually need to dig in and debug some of these steps themselves.

Using Synopsys VCS for 4-state RTL simulation

Using the PyMTL simulation framework can give us a good foundation in

verifying a design. However, the PyMTL RTL simulation that you may be

accustomed to in ECE 4750 is only a 2-state simulation, meaning a signal

can only be 0 or 1. An alternative form of RTL simulation is a

4-state simulation, in which signals can be 0, 1, x, or z.

It is important to note a key difference between 2-state and 4-state

simulation. In 2-state simulation, each variable is initialized to a

determined value. This initial condition assumption may or may not be

what happens in actual silicon! As a result, a different initial condition

could introduce a bug that was not caught by our PyMTL3 2-state RTL

simulation. In 4-state simulations no such assumptions are made. Instead,

every signal begins as x, and only resolves to a 0 or 1 after it

is driven or resolved using x-propagation.

always @(*)

begin

if ( control_signal )

// set signal "signal_a", but bug causes chip to fail

else

// set signal "signal_a" such that everything works fine

end

Look at the above pseudocode. If control_signal is not reset, then in

2-state simulation if you initialize all state to zero it will look like

the chip works fine, but this is not a safe assumption! The real chip

does not guarantee that all state is initialized to zero, so we can model

that in four state simulation as an x. Since the control signal could

initialize to 1, this could non-deterministically cause the chip to fail!

What you would see in simulation is that signal_a would become an x,

because we do not know the value of control_signal on reset. This x is

propogated through the design, and some simulators are more optimistic/pessimistic

about x’s than others. For example, a pessimistic simulator may just assume

that any piece of logic that has an x on the input, outputs an x. This is

pessimistic because it is possible that you can still resolve the output

(imagine a mux where two inputs are the same but the select bit is an x).

Optimism is the opposite, resolving signals to 0 or 1 that

should remain an x.

You may notice in your designs that you are passing all 2-state simulations,

but fail every 4-state simulation. Oftentimes the key to this is that an

output is an x for some cycle, which is a good sign you are not handling

reset properly. We consider it best practice to force invalid output data

to zero, to avoid x’s in your 4-state simulation, and provide a

deterministic output for every cycle no matter the initial condition.

To create a 4-state simulation, let’s start by creating another build directory for our vcs work.

% mkdir -p $TOPDIR/asic-manual/vcs-rtl-build

% cd $TOPDIR/asic-manual/vcs-rtl-build

We run vcs to compile a simulation, and ./simv to run the simulation.

Let’s run a 4-state simulation for test_basic using the design

SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8__pickled.v.

% vcs ../../sim/build/SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8__pickled.v -full64 -sverilog +incdir+../../sim/build +lint=all -xprop=tmerge -top SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_tb ../../sim/build/SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_test_basic_tb.v +vcs+dumpvars+SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_test_basic_vcs.vcd -override_timescale=1ns/1ns

% ./simv

Synopsys VCS is an extremely in-depth tool with many command line options. If you want to learn more on your own about other options that are available to you with VCS, you can visit the course webpage here. However, we’ve detailed some of the key command line options below:

../../sim/build/SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8__pickled.v -The path to the source RTL file

-sverilog -Indicates that we are using SystemVerilog

+incdir+../../sim/build -Specifies directories that contain files that are tagged with `include. We include ../../sim/build because our VTB

includes a _tb.v.cases file located within the ../../sim/build directory

-xprop=tmerge -Specifies that we want to use the tmerge truth table for x-propagation (see VCS user manual for more info)

-top SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_tb -Indicates the name of the top module (located within the VTB)

../../sim/build/SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_test_basic_tb.v -The path to the source testbench file

+define+<macro> -defines a macro that may be used in your verilog code or testbench

+vcs+dumpvars+<filename>.vcd -Tells VCS to dump a VCD in the current dir with the name <filename>.vcd

-override_timescale=1ns/1ns -Changes the timescale. Units/precision

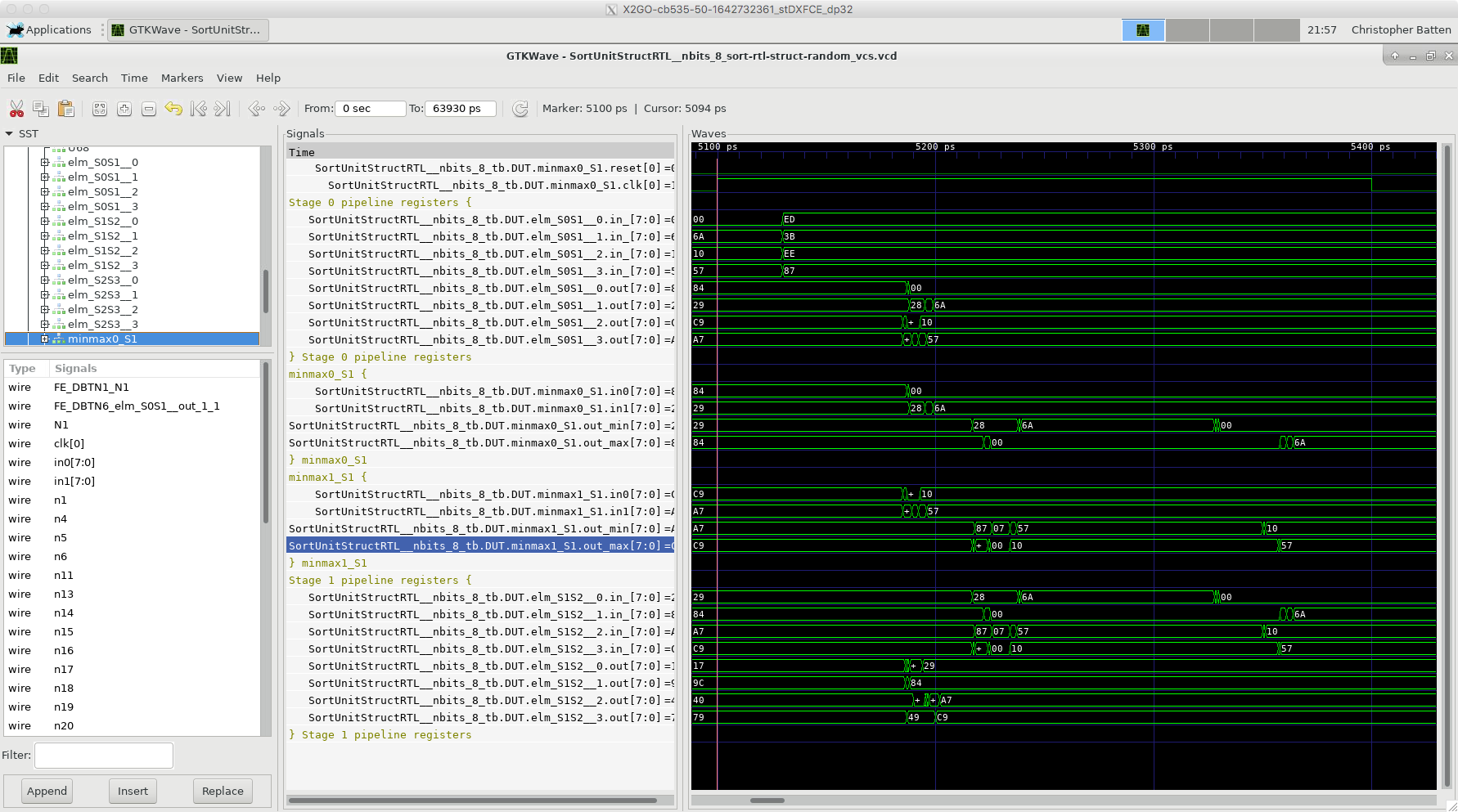

Let’s run another 4-state simulation, this time using the testbench from the sort-rtl simulator run that we ran earlier. Note that while we can use this vcd for power analysis, for the purposes of this tutorial we will only be doing power analysis on the final gate-level netlist that we’ll obtain from Cadence Innovus.

% vcs ../../sim/build/SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8__pickled.v -full64 -sverilog +incdir+../../sim/build +lint=all -xprop=tmerge -top SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_tb ../../sim/build/SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_sort-rtl-struct-random_tb.v +vcs+dumpvars+SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_sort-rtl-struct-random_vcs.vcd -override_timescale=1ns/1ns

% ./simv

Using Synopsys Design Compiler for Synthesis

We use Synopsys Design Compiler (DC) to synthesize Verilog RTL models

into a gate-level netlist where all of the gates are from the standard

cell library. So Synopsys DC will synthesize the Verilog + operator

into a specific arithmetic block at the gate-level. Based on various

constraints it may synthesize a ripple-carry adder, a carry-look-ahead

adder, or even more advanced parallel-prefix adders.

We start by creating a subdirectory for our work, and then launching Synopsys DC.

% mkdir -p $TOPDIR/asic-manual/synopsys-dc

% cd $TOPDIR/asic-manual/synopsys-dc

% dc_shell-xg-t

To make it easier to copy-and-paste commands from this document, we tell

Synopsys DC to ignore the prefix dc_shell> using the following:

dc_shell> alias "dc_shell>" ""

There are two important variables we need to set before starting to work

in Synopsys DC. The target_library variable specifies the standard

cells that Synopsys DC should use when synthesizing the RTL. The

link_library variable should search the standard cells, but can also

search other cells (e.g., SRAMs) when trying to resolve references in our

design. These other cells are not meant to be available for Synopsys DC

to use during synthesis, but should be used when resolving references.

Including * in the link_library variable indicates that Synopsys DC

should also search all cells inside the design itself when resolving

references.

dc_shell> set_app_var target_library "$env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/stdcells.db"

dc_shell> set_app_var link_library "* $env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/stdcells.db"

Note that we can use $env(ECE5745_STDCELLS) to get access to the

$ECE5745_STDCELLS environment variable which specifies the directory

containing the standard cells, and that we are referencing the abstract

logical and timing views in the .db format.

As an aside, if you want to learn more about any command in any Synopsys

tool, you can simply type man toolname at the shell prompt. We are now

ready to read in the Verilog file which contains the top-level design and

all referenced modules. We do this with two commands. The analyze

command reads the Verilog RTL into an intermediate internal

representation. The elaborate command recursively resolves all of the

module references starting from the top-level module, and also infers

various registers and/or advanced data-path components.

dc_shell> analyze -format sverilog ../../sim/build/SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8__pickled.v

dc_shell> elaborate SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8

We need to create a clock constraint to tell Synopsys DC what our target

cycle time is. Synopsys DC will not synthesize a design to run “as fast

as possible”. Instead, the designer gives Synopsys DC a target cycle time

and the tool will try to meet this constraint while minimizing area and

power. The create_clock command takes the name of the clock signal in

the Verilog (which in this course will always be clk), the label to

give this clock (i.e., ideal_clock1), and the target clock period in

nanoseconds. So in this example, we are asking Synopsys DC to see if it

can synthesize the design to run at 3.33GHz (i.e., a cycle time of 300ps).

dc_shell> create_clock clk -name ideal_clock1 -period 0.3

In an ideal world, all inputs and outputs would change immediately with the clock edge. In reality, this is not the case. We need to include reasonable delays for inputs and outputs, so Synopsys DC can factor this into its timing analysis so we would still meet timing if we were to tape our design out in real silicon. Here, we choose 5% of the clock period for our input and output delays.

dc_shell> set_input_delay -clock ideal_clock1 [expr 0.3*0.05] [all_inputs]

dc_shell> set_output_delay -clock ideal_clock1 [expr 0.3*0.05] [all_outputs]

Next, we give Synopsys DC some constraints about fanout and transition slew. Fanout roughly describes the number of inputs driven by a particular output, and the higher the fanout, the higher the drive strength required. Slew rate is how quickly a signal can make a full transition. We want all of our signals to meet a good slew, meaning that they can transition quickly, so we set maximum slew to one quarter of the clock period.

dc_shell> set_max_fanout 20 SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8

dc_shell> set_max_transition [expr 0.25*0.3] SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8

We can use the check_design command to make sure there are no obvious

errors in our Verilog RTL.

dc_shell> check_design

You may see some warnings regarding clk[0] and reset[0] ports not

being connected to any nets in certain modules. This is ok, since in

PyMTL translation we automatically add those ports to all modules, so

they may not actually be used. Aside from this, you should not see any

warnings. However, it is critical that you carefully review all

warnings and errors when you analyze and elaborate a design with Synopsys

DC. There may be many warnings, but you should still skim through them.

Often times there will be something very wrong in your Verilog RTL which

means any results from using the ASIC tools is completely bogus. Synopsys

DC will output a warning, but Synopsys DC will usually just keep going,

potentially producing a completely incorrect gate-level model!

Finally, the compile command will do the synthesis.

dc_shell> compile

During synthesis, Synopsys DC will display information about its optimization process. It will report on its attempts to map the RTL into standard-cells, optimize the resulting gate-level netlist to improve the delay, and then optimize the final design to save area.

The compile command does not flatten your design. Flatten means to

remove module hierarchy boundaries; so instead of having module A and

module B within module C, Synopsys DC will take all of the logic in

module A and module B and put it directly in module C. You can enable

flattening with the -ungroup_all option. Without extra hierarchy

boundaries, Synopsys DC is able to perform more optimizations and

potentially achieve better area, energy, and timing. However, an

unflattened design is much easier to analyze, since if there is a module

A in your RTL design that same module will always be in the synthesized

gate-level netlist.

The compile command does not perform many optimizations. Synopsys DC

also includes compile_ultra which does many more optimizations and will

likely produce higher quality of results. Keep in mind that the compile

command will not flatten your design by default, while the

compile_ultra command will flattened your design by default. You can

turn off flattening by using the -no_autoungroup option with the

compile_ultra command. compile_ultra also has the option -gate_clock

which automatically performs clock gating on your design, which can save

quite a bit of power. Once you finish this tutorial, feel free to go

back and experiment with the compile_ultra command.

Now that we have synthesized the design, we output the resulting

gate-level netlist in two different file formats: Verilog and .ddc

(which we will use with Synopsys DesignVision). We also output an

.sdc file which contains the constraint information we gave synopsys.

We will pass this same constraint information to cadence innovus during

the place and route portion of the flow.

dc_shell> write -format verilog -hierarchy -output post-synth.v

dc_shell> write -format ddc -hierarchy -output post-synth.ddc

dc_shell> write_sdc -nosplit post-synth.sdc

We can use various commands to generate reports about area, energy, and

timing. The report_timing command will show the critical path through

the design. Part of the report is displayed below. Note that this report

was generated using a clock constraint of 300ps.

dc_shell> report_timing -nosplit -transition_time -nets -attributes

...

Point Fanout Trans Incr Path

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

clock ideal_clock1 (rise edge) 0.00 0.00

clock network delay (ideal) 0.00 0.00

elm_S0S1__0/out_reg[5]/CK (DFF_X1) 0.00 0.00 0.00 r

elm_S0S1__0/out_reg[5]/Q (DFF_X1) 0.01 0.09 0.09 r

elm_S0S1__0/out[5] (net) 2 0.00 0.09 r

elm_S0S1__0/out[5] (Reg__Type_Bits8_0) 0.00 0.09 r

elm_S0S1__out[5] (net) 0.00 0.09 r

minmax0_S1/in0[5] (MinMaxUnit__DataType_Bits8_0) 0.00 0.09 r

minmax0_S1/in0[5] (net) 0.00 0.09 r

minmax0_S1/U56/ZN (INV_X1) 0.01 0.03 0.12 f

minmax0_S1/n64 (net) 3 0.00 0.12 f

minmax0_S1/U44/ZN (NAND2_X1) 0.01 0.03 0.14 r

minmax0_S1/n43 (net) 1 0.00 0.14 r

minmax0_S1/U40/ZN (OAI21_X1) 0.01 0.03 0.18 f

minmax0_S1/n44 (net) 2 0.00 0.18 f

minmax0_S1/U47/ZN (NOR2_X1) 0.02 0.04 0.22 r

minmax0_S1/n45 (net) 1 0.00 0.22 r

minmax0_S1/U13/ZN (OAI221_X1) 0.02 0.05 0.27 f

minmax0_S1/n10 (net) 2 0.00 0.27 f

minmax0_S1/U49/ZN (NAND2_X1) 0.03 0.06 0.33 r

minmax0_S1/n59 (net) 6 0.00 0.33 r

minmax0_S1/U69/ZN (OAI22_X1) 0.01 0.04 0.38 f

minmax0_S1/out_min[3] (net) 1 0.00 0.38 f

minmax0_S1/out_min[3] (MinMaxUnit__DataType_Bits8_0) 0.00 0.38 f

minmax0_S1__out_min[3] (net) 0.00 0.38 f

elm_S1S2__0/in_[3] (Reg__Type_Bits8_8) 0.00 0.38 f

elm_S1S2__0/in_[3] (net) 0.00 0.38 f

elm_S1S2__0/out_reg[3]/D (DFF_X1) 0.01 0.01 0.38 f

data arrival time 0.38

clock ideal_clock1 (rise edge) 0.30 0.30

clock network delay (ideal) 0.00 0.30

elm_S1S2__0/out_reg[3]/CK (DFF_X1) 0.00 0.30 r

library setup time -0.04 0.26

data required time 0.26

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

data required time 0.26

data arrival time -0.38

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

slack (VIOLATED) -0.13

This timing report uses static timing analysis to find the critical

path. Static timing analysis checks the timing across all paths in the

design (regardless of whether these paths can actually be used in

practice) and finds the longest path. For more information about static

timing analysis, consult Chapter 1 of the Synopsys Timing Constraints

and Optimization User

Guide. The

report clearly shows that the critical path starts at bit 5 of a pipeline

register in between the S1 and S2 stages (elm_S0S1__0), goes into the

first input of a MinMaxUnit, comes out the out_min port of the

MinMaxUnit, and ends at a pipeline register in between the S1 and S2

stages (elm_S1S2__0). The report shows the delay through each logic

gate (e.g., the clk-to-q delay of the initial DFF is 90ps, the

propagation delay of a NAND2_X1 gate is 30ps) and the total delay for the

critical path which in this case is 0.38ns. Notice that there are two

NAND2_X1 gates, but they do have the same propagation delay; this is

because the static timing analysis also factors in input slew rates, rise

vs fall time, and output load when calculating the delay of each gate. We

set the clock constraint to be 300ps, but also notice that the report

factors in the setup time required at the final register. The setup time

is 40ps, so in order to operate the sort unit at 1ns and meet the setup

time we would need the critical path to arrive in 260ps.

The difference between the required arrival time and the actual arrival time is called the slack. Positive slack means the path arrived before it needed to while negative slack means the path arrived after it needed to. If you end up with negative slack, then you need to rerun the tools with a longer target clock period until you can meet timing with no negative slack. The process of tuning a design to ensure it meets timing is called “timing closure”. In this course we are primarily interested in design-space exploration as opposed to meeting some externally defined target timing specification. So you will need to sweep a range of target clock periods. Your goal is to choose the shortest possible clock period which still meets timing without any negative slack! This will result in a well-optimized design and help identify the “fundamental” performance of the design. Alternatively, if you are comparing multiple designs, sometimes the best situation is to tune the baseline so it has a couple of percent of negative slack and then ensure the alternative designs have similar cycle times. This will enable a fair comparison since all designs will be running at the same cycle time.

The report_area command can show how much area each module uses and can

enable detailed area breakdown analysis.

dc_shell> report_area -nosplit -hierarchy

...

Combinational area: 339.682001

Buf/Inv area: 90.440000

Noncombinational area: 451.401984

Macro/Black Box area: 0.000000

Net Interconnect area: undefined (Wire load has zero net area)

Total cell area: 791.083986

Total area: undefined

Hierarchical area distribution

------------------------------

Global Local

Cell Area Cell Area

---------- ----------------

Hierarchical cell Abs Non Black

Total % Comb Comb Boxes

----------------- ------ ---- ----- ----- --- -------------------------------

SortUnitStructRTL 791.0 100 0.0 0.0 0.0 SortUnitStructRTL__8bit

elm_S0S1__0 36.1 4.6 0.0 36.1 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_0

elm_S0S1__1 36.1 4.6 0.0 36.1 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_11

elm_S0S1__2 36.1 4.6 0.0 36.1 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_10

elm_S0S1__3 36.1 4.6 0.0 36.1 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_9

elm_S1S2__0 36.1 4.6 0.0 36.1 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_8

elm_S1S2__1 36.1 4.6 0.0 36.1 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_7

elm_S1S2__2 36.1 4.6 0.0 36.1 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_6

elm_S1S2__3 36.1 4.6 0.0 36.1 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_5

elm_S2S3__0 36.7 4.6 0.0 36.7 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_4

elm_S2S3__1 37.2 4.7 0.0 37.2 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_3

elm_S2S3__2 37.7 4.8 0.0 37.7 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_2

elm_S2S3__3 36.7 4.6 0.0 36.7 0.0 Reg__Type_Bits8_1

minmax0_S1 75.5 9.5 75.5 0.0 0.0 MinMaxUnit__DataType_Bits8_0

minmax0_S2 72.6 9.2 72.6 0.0 0.0 MinMaxUnit__DataType_Bits8_4

minmax1_S1 71.2 9.0 71.2 0.0 0.0 MinMaxUnit__DataType_Bits8_3

minmax1_S2 72.3 9.1 72.3 0.0 0.0 MinMaxUnit__DataType_Bits8_2

minmax_S3 43.8 5.5 43.8 0.0 0.0 MinMaxUnit__DataType_Bits8_1

val_S0S1 5.8 0.7 1.3 4.5 0.0 RegRst__Type_Bits1__reset_value_0_0

val_S1S2 5.8 0.7 1.3 4.5 0.0 RegRst__Type_Bits1__reset_value_0_2

val_S2S3 5.8 0.7 1.3 4.5 0.0 RegRst__Type_Bits1__reset_value_0_1

----------------- ------ ---- ----- ----- --- -------------------------------

Total 339.6 451.4 0.0

The units are in square micron. The cell area can sometimes be different

from the total area. The total cell area includes just the standard

cells, while the total area can include interconnect area as well. If

available, we will want to use the total area in our analysis. Otherwise

we can just use the cell area. So we can see that the sort unit consumes

approximately 791um^2 of area. We can also see that each pipeline

register consumes about 4-5% of the area, while the MinMaxUnits consume

about ~40% of the area. This is one reason we try not to flatten our

designs, since the module hierarchy helps us understand the area

breakdowns. If we completely flattened the design there would only be one

line in the above table.

The report_power command can show how much power each module consumes.

Note that this power analysis is actually not that useful yet, since at

this stage of the flow the power analysis is based purely on statistical

activity factor estimation. Basically, Synopsys DC assumes every net

toggles 10% of the time. This is a pretty poor estimate, so we should

never use this kind of statistical power estimation in this course.

dc_shell> report_power -nosplit -hierarchy

Finally, we go ahead and exit Synopsys DC.

dc_shell> exit

Take a few minutes to examine the resulting Verilog gate-level netlist.

Notice that the module hierarchy is preserved and also notice that the

MinMaxUnit synthesizes into a large number of basic logic gates.

% cd $TOPDIR/asic-manual/synopsys-dc

% more post-synth.v

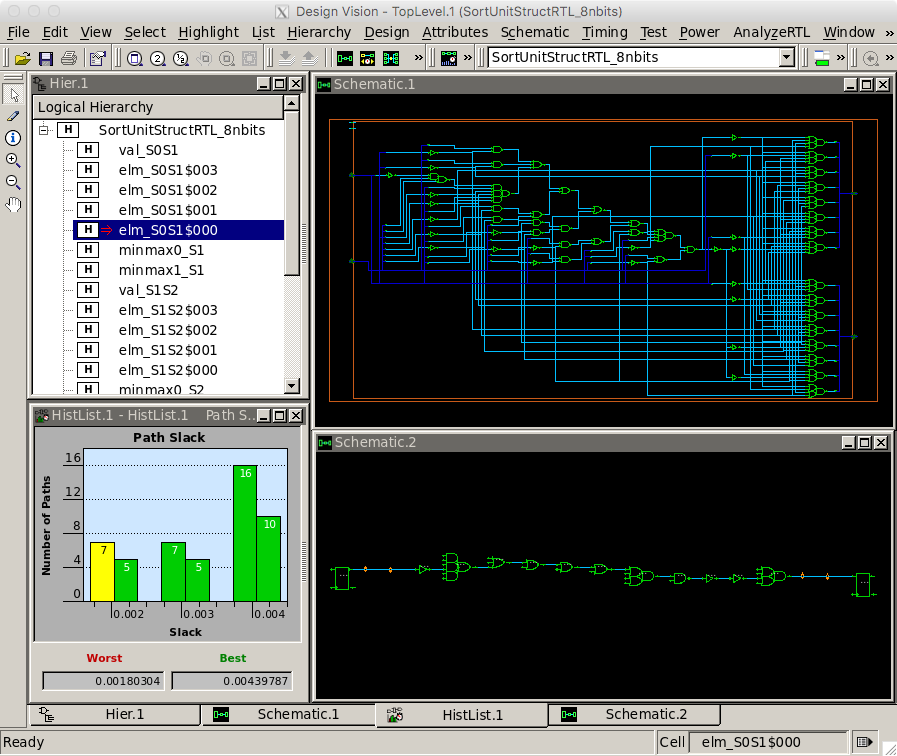

We can use the Synopsys Design Vision (DV) tool for browsing the

resulting gate-level netlist, plotting critical path histograms, and

generally analyzing our design. Start Synopsys DV and setup the

target_library and link_library variables as before.

% cd $TOPDIR/asic-manual/synopsys-dc

% design_vision-xg

design_vision> set_app_var target_library "$env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/stdcells.db"

design_vision> set_app_var link_library "* $env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/stdcells.db"

Choose File > Read from the menu to open post-synth.ddc file

generated during synthesis. You can then use the following steps to view

the gate-level schematic for the MinMaxUnit:

- Select the

minmax0_S1module in the Logical Hierarchy panel - Choose Schematic > New Schematic View from the menu

- Double click the box representing the

MinMaxUnitin the schematic view

This shows you the exact gates used to implement the MinMaxUnit. You

can use the following steps to view a histogram of path slack, and also

to open a gave-level schematic of just the critical path.

- Choose Timing > Path Slack from the menu

- Click OK in the pop-up window

- Select the left-most bar in the histogram to see list of most critical paths

- Right click first path (the critical path) and choose Path Schematic

This shows you the exact gates that lie on the critical path. Notice that there nine levels of logic (including the registers) on the critical path. The number of levels of logic on the critical path can provide some very rough first-order intuition on whether or not we might want to explore a more aggressive clock constraint and/or adding more pipeline stages. If there are just a few levels of logic on the critical path then our design is probably very simple (as in this case!), while if there are more than 50 levels of logic then there is potentially room for signficant improvement. The following screen capture illutrates using Design Vision to explore the post-synthesis results. While this can be interesting, in this course, we almost always prefer exploring the post-place-and-route results, so we will not really use Synopsys DC that often.

To Do On Your Own: Sweep a range of target clock frequencies to

determine the shortest possible clock period which still meets timing

without any negative slack. You can put a sequence of commands in a

.tcl file and then run Synopsys DC using those commands in one step

like this:

% cd $TOPDIR/asic-manual/synopsys-dc

% dc_shell-xg-t -f init.tcl

So consider placing the commands from this section into a .tcl file

and then running Synopsys DC with a target clock period of 0.3ns. Then

gradually increase the clock period until your design meets timing. To

follow along with the tutorial, push the design through synth again using 0.6

ns as your clock constraint, as this is what we will be using for the

rest of the flow.

Using Synopsys VCS for Fast Functional Gate-Level Simulation

Before synthesis, we used Synopsys VCS to do a 4-state simulation. This time, we’ll be using VCS to perform a gate-level simulation, since we now have a gate-level netlist available to us. Gate-level simulation provides an advantage over RTL simulation because it more precisely represents the specification of the true hardware generated by the tools. This sort of simulation could propogate X’s into the design that were not found by the 4-state RTL simulation, and it also verifies that the tools did not optimize anything away during synthesis. A fast-functional simulation is a zero delay simulation which provides a way to check functionality at the gate level without worrying about the timing checks involved in a back-annotated gate-level simulation, which we’ll perfrom later in this tutorial.

We’ll start by creating a build directory for our post-synth run of vcs.

% mkdir -p $TOPDIR/asic-manual/vcs-postsyn-build

% cd $TOPDIR/asic-manual/vcs-postsyn-build

Then we’ll run vcs and ./simv to run our gate-level simulation on the sort-rtl-struct-random simulator testbench:

% vcs ../synopsys-dc/post-synth.v $ECE5745_STDCELLS/stdcells.v -full64 -sverilog +incdir+../../sim/build +lint=all -xprop=tmerge -top SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_tb ../../sim/build/SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_sort-rtl-struct-random_tb.v +define+CYCLE_TIME=0.6 +define+VTB_INPUT_DELAY=0.03 +define+VTB_OUTPUT_ASSERT_DELAY=0.57 +delay_mode_zero +vcs+dumpvars+SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8_sort-rtl-struct-random_vcs.vcd -override_timescale=1ns/1ps

% ./simv

Notice there are some differences in the vcs command we ran here, and the

one we ran for 4-state RTL simulation. In this version, we use the

gate-level netlist post-synth.v instead of the pickled file. We also include

the option +delay_mode_zero which tells vcs to run a fast-functional simulation

in which no delays are considered. This is similar to RTL simulation, and you

should notice that all signals will change on the clock edge. We also include the

macros CYCLE_TIME, VTB_INPUT_DELAY , VTB_OUTPUT_ASSERT_DELAY. These values

are not actually critical for a fast-functional simulation, but we set them to the

same values as the Back-Annotated gate-level simulations to make comparing vcd’s

easier when debugging.

Using Cadence Innovus for Place-and-Route

We use Cadence Innovus for placing standard cells in rows and then automatically routing all of the nets between these standard cells. We also use Cadence Innovus to route the power and ground rails in a grid and connect this grid to the power and ground pins of each standard cell, and to automatically generate a clock tree to distribute the clock to all sequential state elements with hopefully low skew.

We will be running Cadence Innovus in a separate directory to keep the files separate from the other tools.

% mkdir -p $TOPDIR/asic-manual/cadence-innovus

% cd $TOPDIR/asic-manual/cadence-innovus

Before starting Cadence Innovus, we need two files which will be loaded

into the tool. The first file is a .sdc file which contains timing

constraint information about our design. This file is where we specify

our target clock period, but it is also where we could specify input or

output delay constraints (e.g., the output signals must be stable 200ps

before the rising edge). We created this file at the end of our synthesis

step using Synopsys DC. Before we get started, let’s open that file to

take a look at the constraint DC generated.

% less ../synopsys-dc/post-synth.sdc

The create_clock command is similar to the command we used in synthesis, and we usually use the same target clock period that we used for synthesis. In this case, we are targeting a 1.67GHz clock frequency (i.e., a 0.6ns clock period). Note that we also see the constraints that we set for input and output delay, max fanout, max transition as well as our path groups.

The second file is a “multi-mode multi-corner” (MMMC) analysis file. This

file specifies what “corner” to use for our timing analysis. A corner is

a characterization of the standard cell library and technology with

specific assumptions about the process, temperature, and voltage (PVT).

So we might have a “fast” corner which assumes best-case process

variability, low temperature, and high voltage, or we might have a “slow”

corner which assumes worst-case variability, high temperature, and low

voltage. To ensure our design will work across a range of operating

conditions, we need to evaluate our design across a range of corners. In

this course, we will keep things simple by only considering a “typical”

corner (i.e., average PVT). Use Geany or your favorite text editor to

create a file named setup-timing.tcl in

$TOPDIR/asic-manual/cadence-innovus with the following content:

create_rc_corner -name typical \

-cap_table "$env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/rtk-typical.captable" \

-T 25

create_library_set -name libs_typical \

-timing [list "$env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/stdcells.lib"]

create_delay_corner -name delay_default \

-early_library_set libs_typical \

-late_library_set libs_typical \

-rc_corner typical

create_constraint_mode -name constraints_default \

-sdc_files [list ../synopsys-dc/post-synth.sdc]

create_analysis_view -name analysis_default \

-constraint_mode constraints_default \

-delay_corner delay_default

set_analysis_view \

-setup [list analysis_default] \

-hold [list analysis_default]

The create_rc_corner command loads in the .captable file that we

examined earlier. This file includes information about the resistance and

capacitance of every metal layer. Notice that we are loading in the

“typical” captable and we are specifying an “average” operating

temperature of 25 degC. The create_library_set command loads in the

.lib file that we examined earlier. This file includes information

about the input/output capacitance of each pin in each standard cell

along with the delay from every input to every output in the standard

cell. The create_delay_corner specifies a specific corner that we would

like to use for our timing analysis by putting together a .captable and

a .lib file. In this specific example, we are creating a typical corner

by putting together the typical .captable and typical .lib we just

loaded. The create_constraint_mode command loads in the .sdc file we

mentioned earlier in this section. The create_analysis_view command

puts together constraints with a specific corner, and the

set_analysis_view command tells Cadence Innovus that we would like to

use this specific analysis view for both setup and hold time analysis.

Now that we have created our setup-timing.tcl

file we can start Cadence Innovus:

% cd $TOPDIR/asic-manual/cadence-innovus

% innovus -64

As we enter commands we will be able use the GUI to see incremental

progress towards a fully placed-and-routed design. We need to set various

variables before starting to work in Cadence Innovus. These variables

tell Cadence Innovus the location of the MMMC file, the location of the

Verilog gate-level netlist, the name of the top-level module in our

design, the location of the .lef files, and finally the names of the

power and ground nets.

innovus> set init_mmmc_file "setup-timing.tcl"

innovus> set init_verilog "../synopsys-dc/post-synth.v"

innovus> set init_top_cell "SortUnitStructRTL__nbits_8"

innovus> set init_lef_file "$env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/rtk-tech.lef $env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/stdcells.lef"

innovus> set init_gnd_net "VSS"

innovus> set init_pwr_net "VDD"

We are now ready to use the init_design command to read in the verilog,

set the design name, setup the timing analysis views, read the technology

.lef for layer information, and read the standard cell .lef for

physical information about each cell used in the design.

innovus> init_design

Then, we tell innovus the type of timing analysis we want it to do. In on-chip variation (OCV) mode, the software calculates clock and data path delays based on minimum and maximum operating conditions for setup analysis and vice-versa for hold analysis. These delays are used together in the analysis of each check. The OCV is the small difference in the operating parameter value across the chip. Each timing arc in the design can have an early and a late delay to account for the on-chip process, voltage, and temperature variation. We need this mode in order to do proper hold time fixing later on.

innovus> setAnalysisMode -analysisType onChipVariation -cppr both

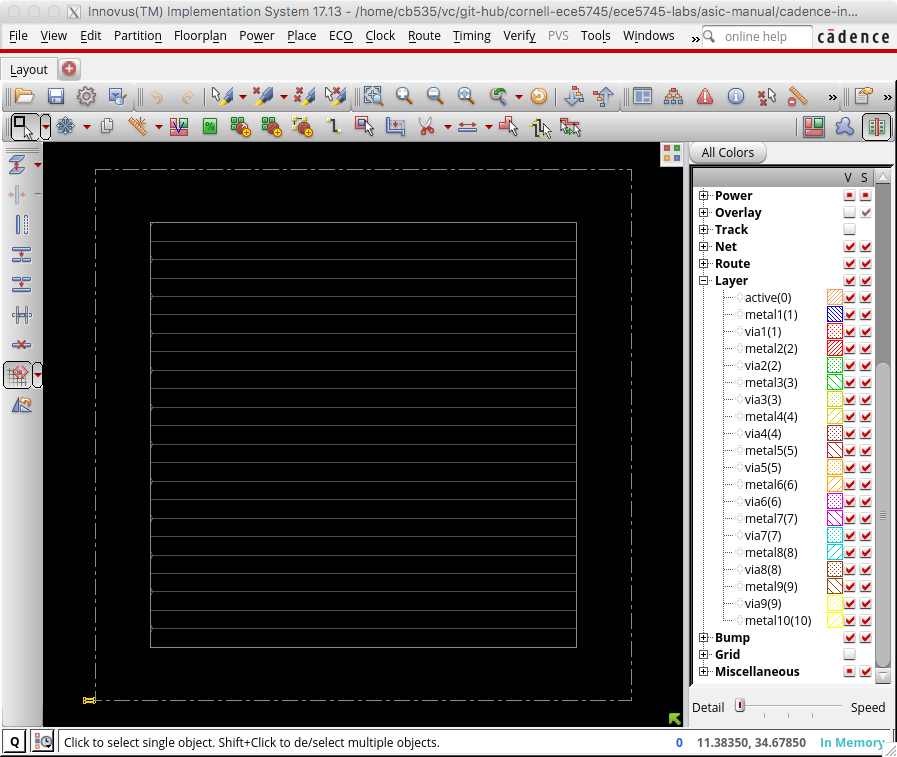

The next step is to do some floorplaning. This is where we broadly

organize the chip in terms of its overall dimensions and the placement of

any previously designed blocks. For now we just do some very simple

floorplanning using the floorPlan command.

innovus> floorPlan -r 1.0 0.70 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0

In this example, we have chosen the aspect ratio to be 1.0 and a target cell utilization to be 70%. The cell utilization is the percentage of the final chip that will actually contain useful standard cells as opposed to just “filler” cells (i.e., empty cells). Ideally, we would like the cell utilization to be 100% but this is simply not reasonable. If the cell utilization is too high, Cadence Innovus will spend way too much time trying to optimize the design and will eventually simply give up. A target cell utilization of 70% makes it more likely that Cadence Innovus can successfuly place and route the design. We have also added 4.0um of margin around the top, bottom, left, and right of the chip to give us room for the power ring which will go around the entire chip.

The following screen capture illustrates what you should see: a square floorplan with rows where the standard cells will eventually be placed. You can use the View > Fit menu option to see the entire chip.

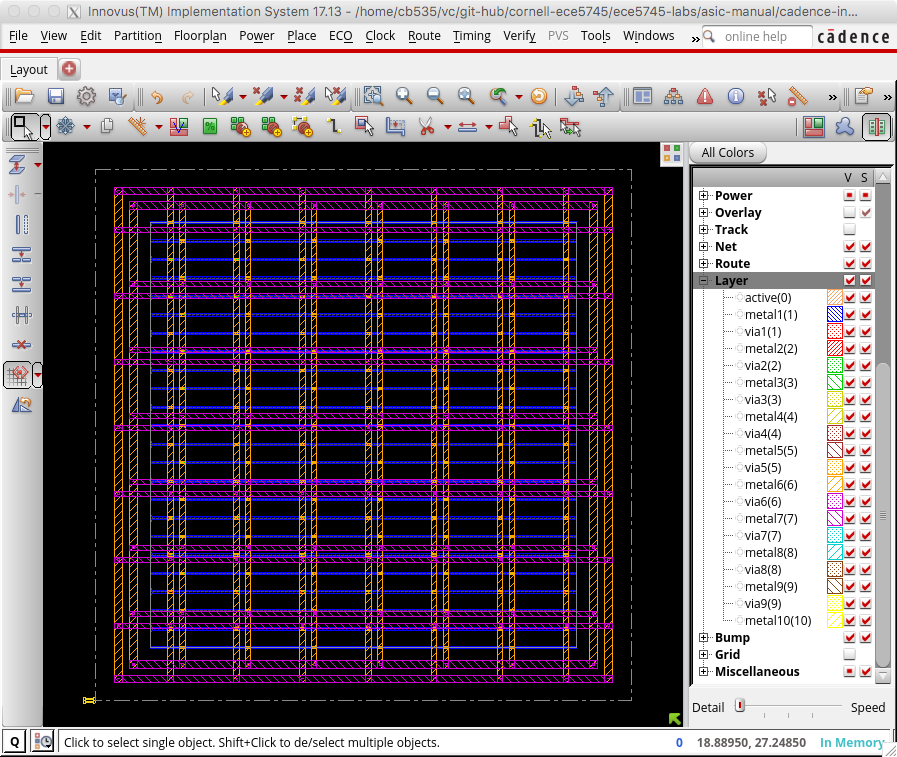

The next step is to work on power routing. Recall that each standard cell

has internal M1 power and ground rails which will connect via abutment

when the cells are placed into rows. If we were just to supply power to

cells using these rails we would likely have large IR drop and the cells

in the middle of the chip would effectively be operating at a much lower

voltage. During power routing, we create a grid of power and ground wires

on the top metal layers and then connect this grid down to the M1 power

rails in each row. We also create a power ring around the entire

floorplan. Before doing the power routing, we need to use the

globalNetCommand command to tell Cadence Innovus which nets are power

and which nets are ground (there are many possible names for power and

ground!).

innovus> globalNetConnect VDD -type pgpin -pin VDD -inst * -verbose

innovus> globalNetConnect VSS -type pgpin -pin VSS -inst * -verbose

We can now draw M1 “rails” for the power and ground rails that go along each row of standard cells.

innovus> sroute -nets {VDD VSS}

We now create a power ring around our chip using the addRing command. A

power ring ensures we can easily get power and ground to all standard

cells. The command takes parameters specifying the width of each wire in

the ring, the spacing between the two rings, and what metal layers to use

for the ring. We will put the power ring on M6 and M7; we often put the

power routing on the top metal layers since these are fundamentally

global routes and these top layers have low resistance which helps us

minimize static IR drop and di/dt noise. These top layers have high

capacitance but this is not an issue since the power and ground rails are

not switching (and indeed this extra capacitance can serve as a very

modest amount of decoupling capacitance to smooth out time variations in

the power supply).

innovus> addRing -nets {VDD VSS} -width 0.6 -spacing 0.5 \

-layer [list top 7 bottom 7 left 6 right 6]

We have power and ground rails along each row of standard cells and a

power ring, so now we need to hook these up. We can use the addStripe

command to draw wires and automatically insert vias whenever wires cross.

First, we draw the vertical “stripes”.

innovus> addStripe -nets {VSS VDD} -layer 6 -direction vertical \

-width 0.4 -spacing 0.5 -set_to_set_distance 5 -start 0.5

And then we draw the horizontal “stripes”.

innovus> addStripe -nets {VSS VDD} -layer 7 -direction horizontal \

-width 0.4 -spacing 0.5 -set_to_set_distance 5 -start 0.5

The following screen capture illustrates what you should see: a power ring and grid on M6 and M7 connected to the horizontal power and ground rails on M1.

You can toggle the visibility of metal layers by using the panel on the right. Click the checkbox in the V column to toggle the visibility of the corresponding layer. You can also simply use the number keys on your keyboard. Pressing the 6 key will toggle M6 and pressing the 7 key will toggle M7. Zoom in on a via and toggle the visibility of the metal layers to see how Cadence Innovus has automatically inserted a via stack that goes from M1 all the way up to M6 or M7.

Now that we have finished our basic power planning we can do the initial

placement and routing of the standard cells using the place_design

command:

innovus> place_design

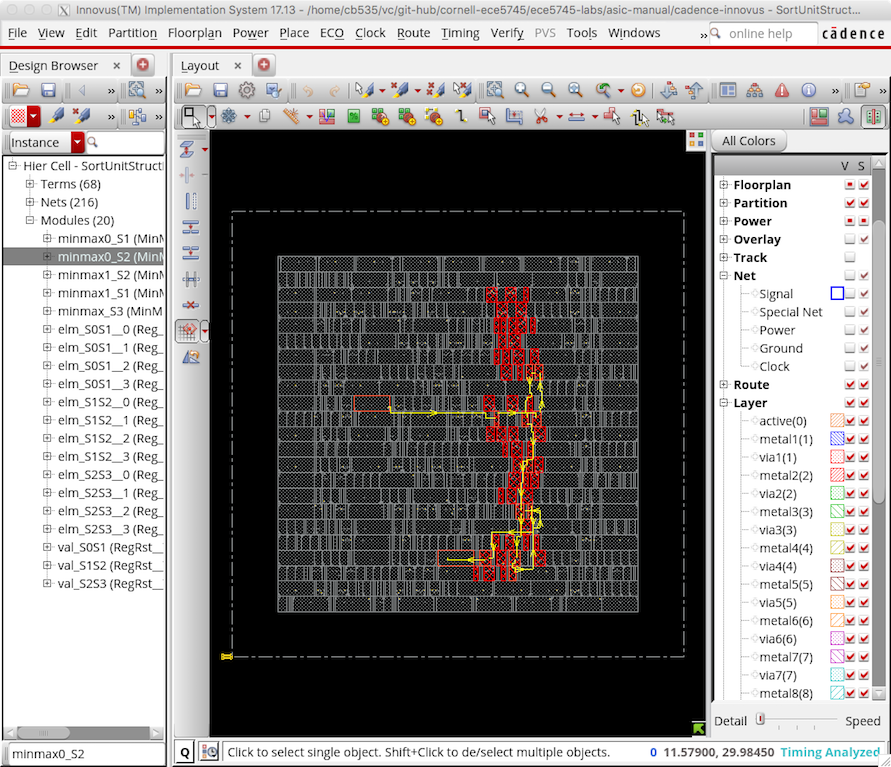

The following screen capture illustrates what you should see: the gates have been placed underneath a sea of wiring on the various metal layers.

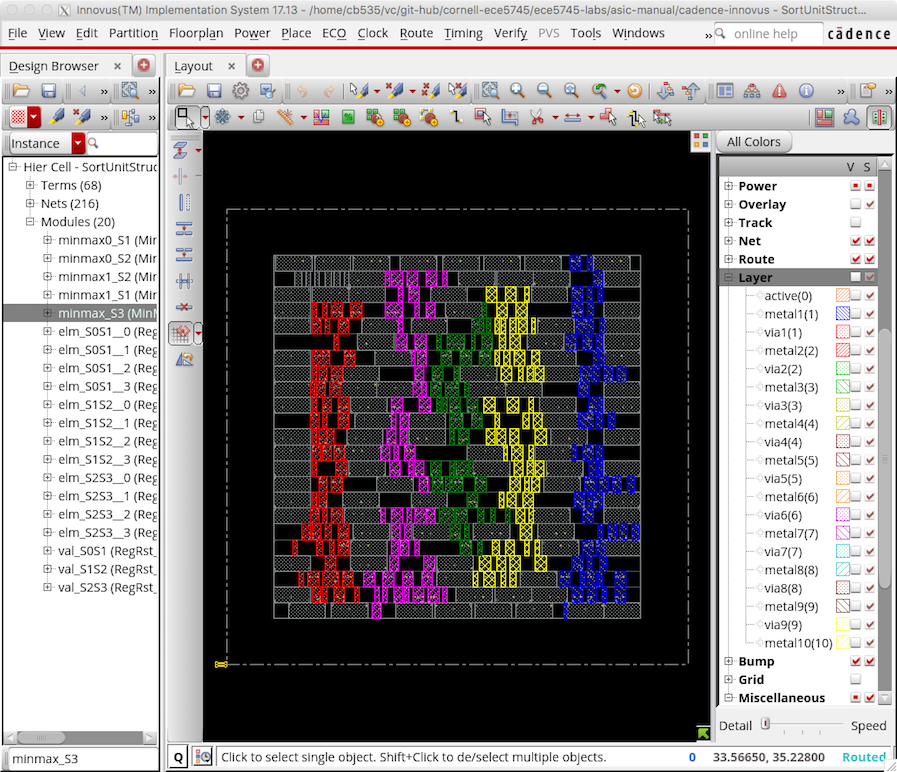

Note that Cadence Innovus has only done a very preliminary routing, primarily to help improve placement. You can use the Amobea workspace to help visualize how modules are mapped across the chip. Choose Windows > Workspaces > Amoeba from the menu. However, we recommend using the design browser to help visualize how modules are mapped across the chip. Here are the steps:

- Choose Windows > Workspaces > Design Browser + Physical from the menu

- Hide all of the metal layers by pressing the number keys

- Browse the design hierarchy using the panel on the left

- Right click on a module, click Highlight, select a color

In this way you can view where various modules are located on the chip.

The following screen capture illustrates the location of the five

MinMaxUnit modules.

Notice how Cadence Innovus has grouped each module together. The placement algorithm tries to keep connected standard cells close together to minimize wiring.

The next step is to assign IO pin location for our block-level design. Since this is not a full chip with IOcells, or a hierarchical block, we don’t really care exactly where all of the pins line up, so we’ll let the tool assign the location for all of the pins.

innovus> assignIoPins -pin *

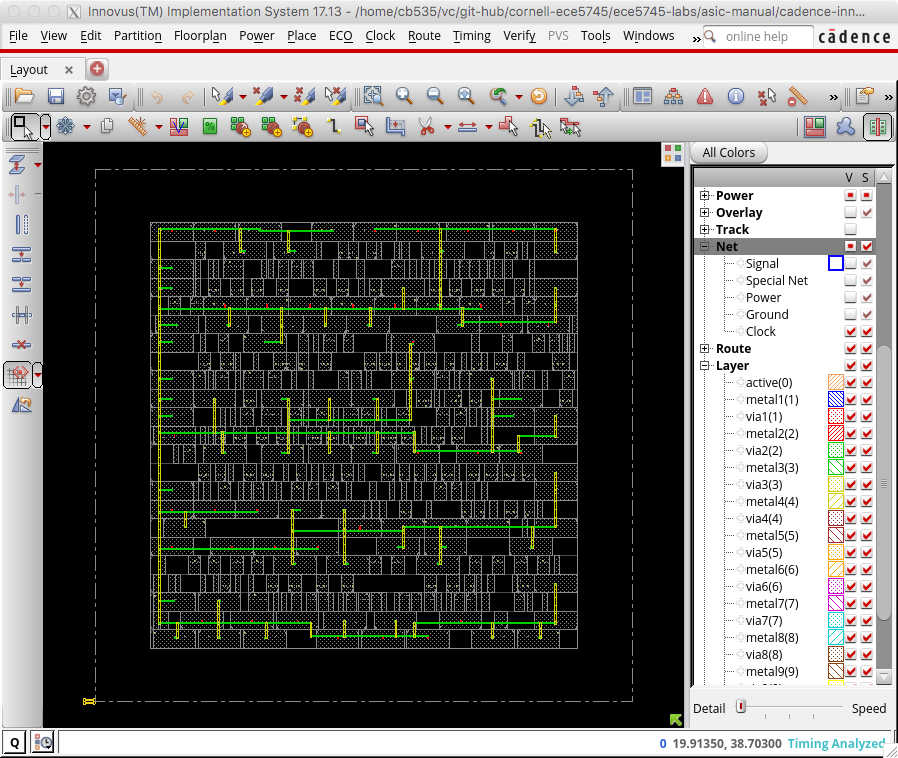

The next step is to improve the quality of the clock tree routing. First,

let’s display just the clock tree so we can clearly see the impact of

optimized clock tree routing. In the right panel click on Net and then

deselect the checkbox in the V column next to Signal, Special Net,

Power, and Ground so that only Clock is selected. You should be

able to see the clock snaking around the chip connecting the clock port

of all of the registers. Now use the ccopt_design command to optimize

the clock tree routing.

innovus> ccopt_design

If you watch closely you should see a significant difference in the clock tree routing before and after optimization. The following screen capture illustrates the optimized clock tree routing.

The routes are straighter, shorter, and well balanced. This will result in much lower clock skew.

To avoid hold time violations (situations where the contamination delay is smaller than the hold time and new data arrives too quickly) we include the following commands:

innovus> setOptMode -holdFixingCells {BUF_X1}

innovus> setOptMode -holdTargetSlack 0.013 -setupTargetSlack 0.044;

innovus> optDesign -postCTS -outDir timingReports -prefix postCTS_hold -hold

Here, we specified a list of buffer cells to the tool from stdcells.v that

innovus can use to add in delays to paths that violate the hold time

constraint. We then tell innovus our hold and setup time constraints, in

nanoseconds, these numbers were derived from the .lib file. Then, we

actually fix any violating paths using the optDesign command.

If you look into the output of optDesign, you should see the following section:

*** Finished Core Fixing (fixHold) cpu=0:00:00.6 real=0:00:01.0 totSessionCpu=0:01:30 mem=1745.2M density=71.079% ***

*info:

*info: Added a total of 51 cells to fix/reduce hold violation

*info:

*info: Summary:

*info: 51 cells of type ‘BUF_X1’ used

This means that as a result of our hold time optimization, we have added 51 buffer cells to the netlist.

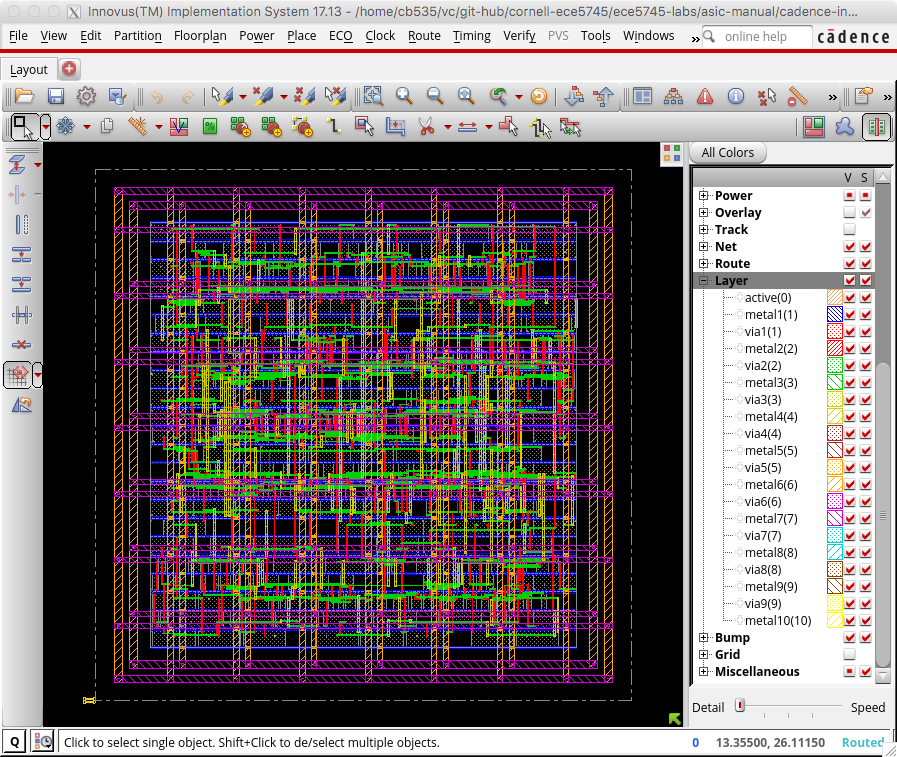

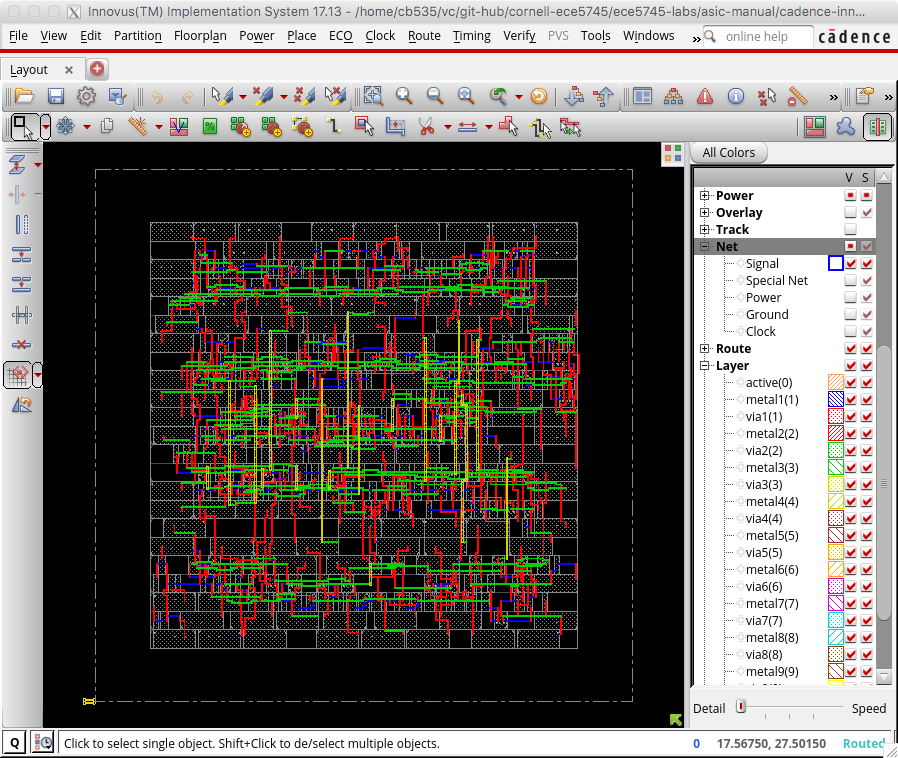

The next step is to improve the quality of the signal routing. Display

just the signals but not the power and ground routing by clicking on the

checkbox in the V column next to Signal in the left panel. Then use the

routeDesign command to optimize the signal routing. We follow this with

another iteration of optDesign to fix any violating paths that were

created during routeDesign.

innovus> routeDesign

innovus> optDesign -postRoute -outDir timingReports -prefix postRoute_hold -hold

If you watch closely you should see a significant difference in the signal routing before and after optimization. The following screen capture illustrates the optimized signal routing.

Again the routes are straighter and shorter. This will reduce the interconnect resistance and capacitance and thus improve the delay and energy of our design.

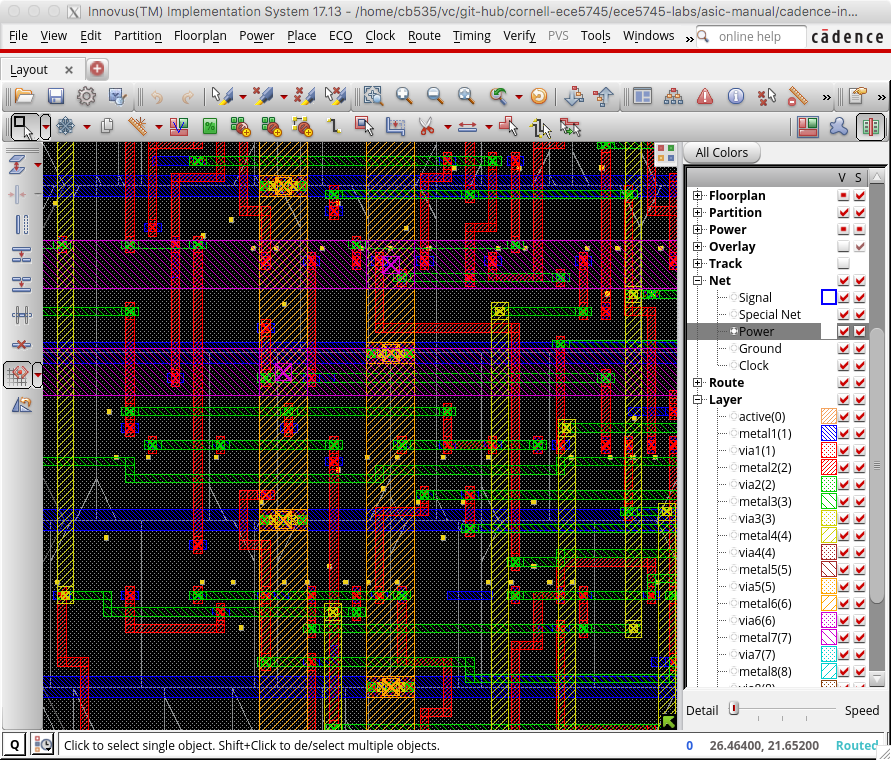

The final step is to insert “filler” cells. Filler cells are essentially empty standard cells whose sole purpose is to connect the wells across each standard cell row.

innovus> setFillerMode -corePrefix FILL -core "FILLCELL_X4 FILLCELL_X2 FILLCELL_X1"

innovus> addFiller

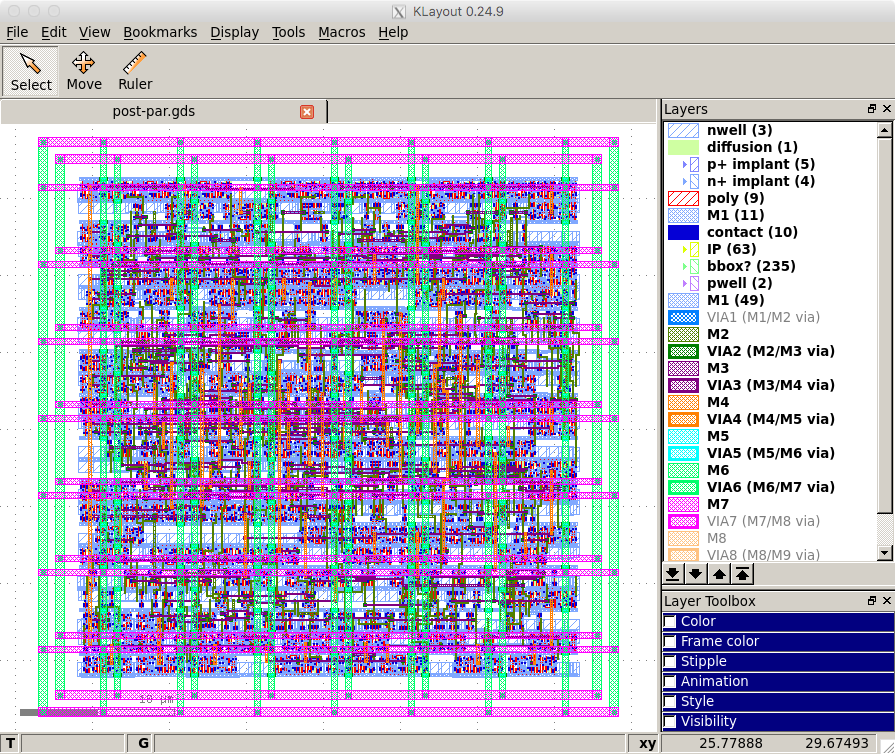

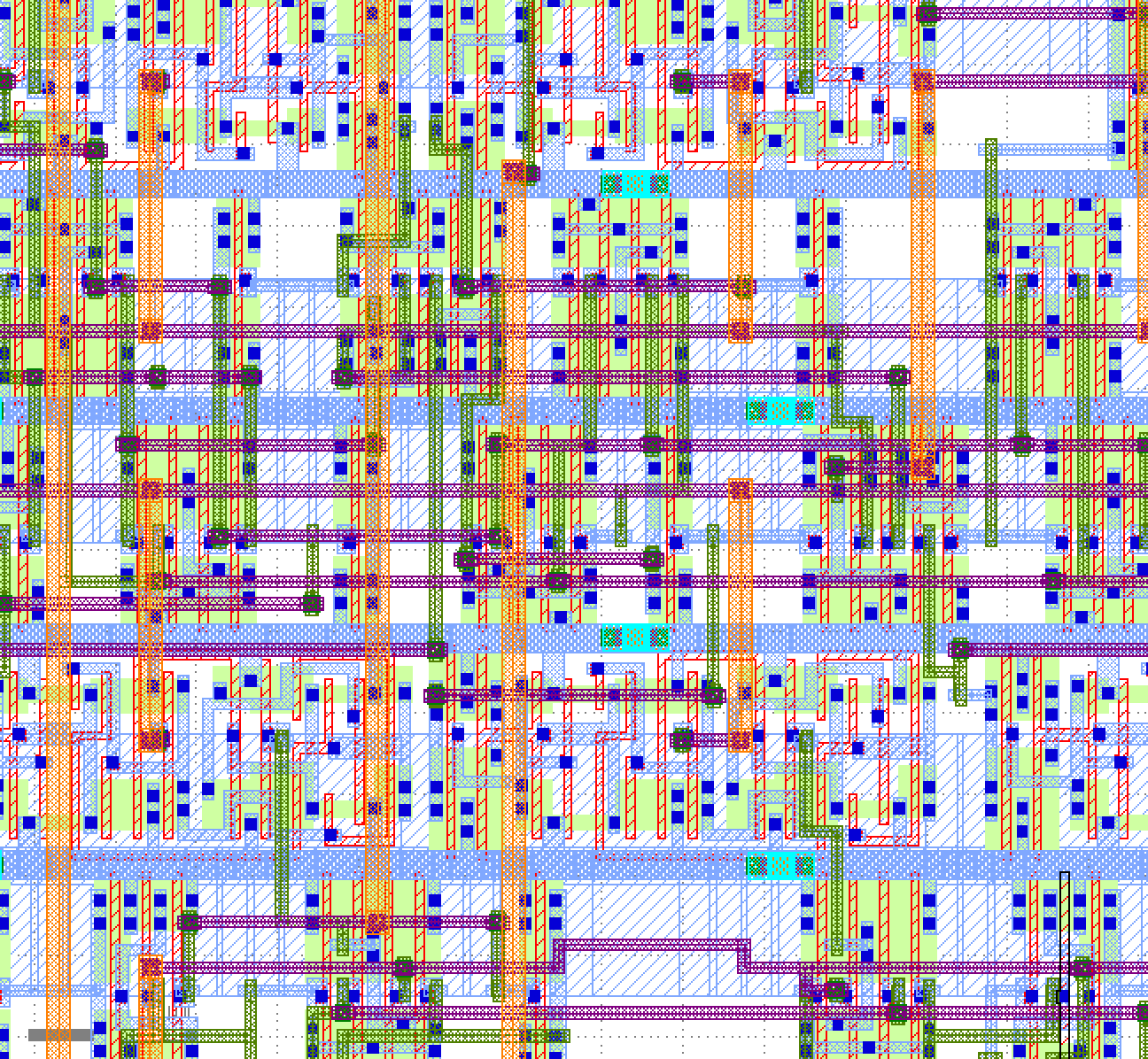

Zoom in to see some of the detailed routing and take a moment to appreciate how much effort the tools have done for us automatically to synthesize, place, and route this design. The following screen capture shows some of this detailed routing.

Notice how each metal layer always goes in the same direction. So M2 is always vertical, M3 is always horizontal, M4 is always vertical, etc. This helps reduce capacitive coupling across layers and also simplifies the routing algorithm. Actually, if you look closely in the above screen shot you can see situations on M2 (red) and M3 (green) where the router has generated a little “jog” meaning that on a single layer the wire goes both vertically and horizontally. This is an example of the sophisticated algorithms used in these tools.

Our design is now on silicon! Obviously there are many more steps required before you can really tape out a chip. We would need to add an I/O ring with pads so we can connect the chip to the package, we would need to do further verification, and additional optimization.

For example, one thing we want to do is verify that the gate-level

netlist matches what is really in the final layout. We can do this using

the verifyConnectivity command. We can also do a preliminary “design

rule check” to make sure that the generated metal interconnect does not

violate any design rules with the verify_drc command.

innovus> verifyConnectivity

innovus> verify_drc

Now we can generate various output files. We might want to save the final gate-level netlist for the chip, since Cadence Innovus will often insert new cells or change cells during its optimization passes.

innovus> saveNetlist post-par.v

We can also extract resistance and capacitance for the metal interconnect

and write this to a special .spef file. This file can be used for later

timing and/or power analysis.

innovus> extractRC

innovus> rcOut -rc_corner typical -spef post-par.spef

You may get an error regarding open nets. This is actually more of a warning message, and for the purposes of RC extraction we can ignore this.

We also need to extract delay information and write this to an

.sdf(Standard Delay Format) file, which we’ll use for our

back-annotated gate-level simulations.

innovus> write_sdf post-par.sdf -interconn all -setuphold split

Finally, we of course need to generate the real layout as a .gds file. This

is what we will send to the foundry when we are ready to tapeout the

chip.

innovus> streamOut post-par.gds \

-merge "$env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/stdcells.gds" \

-mapFile "$env(ECE5745_STDCELLS)/rtk-stream-out.map"

We can also use Cadence Innovus to do timing, area, and power analysis similar to what we did with Synopsys DC. These post-place-and-route results will be much more accurate than the preliminary post-synthesis results. Let’s start with a basic timing report.

innovus> report_timing

...

Other End Arrival Time 0.000

- Setup 0.045

+ Phase Shift 0.600

= Required Time 0.555

- Arrival Time 0.502

= Slack Time 0.053

Clock Rise Edge 0.000

+ Clock Network Latency (Prop) 0.000

= Beginpoint Arrival Time 0.000

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Instance | Arc | Cell | Delay | Arrival | Required |

| | | | | Time | Time |

|----------------------------------------+--------------+----------+-------+---------+----------|

| elm_S1S2__2/out_reg[3] | CK ^ | | | 0.000 | 0.053 |